The name is positively exotic. Rhinella Marina.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

A Greek actress perhaps? Or a Latin philosopher?

You couldn't be further from the truth. It is in fact ... drumroll please ... the scientific name for the cane toad, probably the most despised creature in Australia today.

They're suddenly in the news here in the Lower Hunter following three recent sightings.

The first two were in Metford in January, one of which resulted in the painful death of the family's much loved French Bulldog, Rose.

Shortly after another was spotted in Medowie. Like it or not, Rhinella Marina has arrived.

Which raises the question of whether - despite having science, the CSIRO, research grants, superior intelligence and a committed national desire behind us - we have been beaten by what is essentially a pugnacious frog?

After all, since the cane toad started spreading west and south from its North Queensland "home", there has been significant time and money put into stopping its relentless migration.

Kakadu, in particular - the jewel in Australia's ecological crown - had to be protected. But to no avail. These days the top half of Australia is cane toad territory.

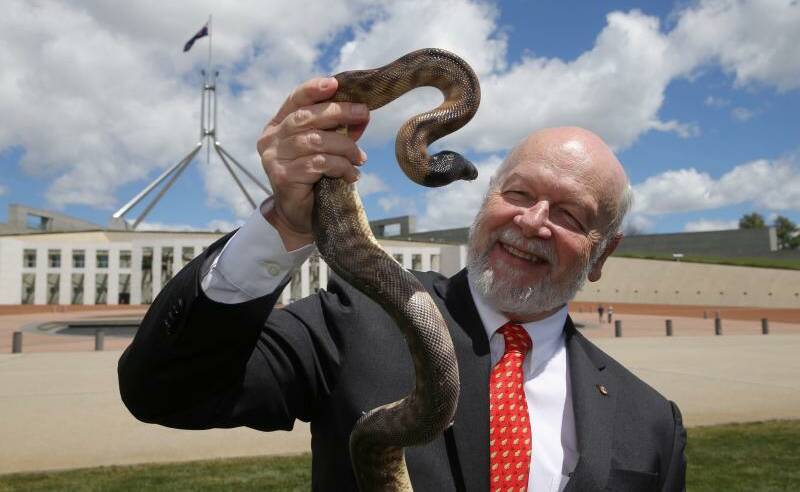

One of the foremost experts on the cane toad is Rick Shine, an evolutionary biologist and ecologist, and Professor at Macquarie University.

Born in Queensland, he was brought to loathe the Brazilian native, yet he admits to a certain respect for the little guys.

"An imported species that has proved so resilient," he said. "You've got to admire that. Don't get me wrong, I've been devastated at times, heartbroken even, by the swathe of native animals I've seen lying around dead as the cane toad's habitat has spread.

"But let's not forget we brought them here. They're not the devil incarnate, they kill in self defence."

That defence he refers to is a deadly toxin emitted through the skin, mostly from around the shoulder area, that can ravage the native wildlife population. Snakes, goannas, lizards, quolls, even freshwater crocodiles, have suffered very significant population loss.

Cane toads were originally imported into Australia in 1935 to kill the beetles that were eating the valuable sugar cane crops in north Queensland. But no-one could imagine the effect a measly 101 imported cane toads would have.

Consider this: females can lay up to 30,000 eggs at a time. And for years - decades really - the best way to eradicate them was by hand, one at a time. See the problem? Their spread was inevitable.

Today virtually all of northern Australia has been "conquered".

"They're great travellers," Professor Shine says. "Water is the key thing for them. They can't be far from water ... take that away and they're in trouble."

But if that is a problem, they have one major advantage. They love to hitch a ride on the back of a truck, which means they can be in the next state overnight. And they're tough little customers. Cold, heat, wind ... conditions that would kill other species, they'll handle no problem.

Their relentless spread has come at great cost to native wildlife who feed on native frogs. Images of dead wildlife are burned into Professor Shine's mind.

"Fortunately no species has been wiped out, but massive numbers have been lost," he concedes.

Still, the ecologist can see an up side.

"We'll see thousands of goannas killed for example, but suddenly these other species that have been under pressure can thrive. The black headed python is one. Their numbers have really bounced back strongly which was good to see."

While all this has been going on, there has been frantic research activity aimed at negating their impact, but they're an incredibly resilient foe. And how do you kill off a cane toad but not the biologically similar frog which inhabits the same territory and is so important to our ecosystem?

There have been quite a few ideas bounced around.

One is to genetically interfere with the future generation of cane toads. Make all the their offspring males for example, or sterile. But there has been limited support for this approach - it would seem that biological interference might be a step too far.

Professor Shine has been at the cutting edge of much of this discussion and fancies a multi-pronged attack.

Firstly, he wants to give natural evolution a nudge along, aided by ... wait for it ... a sausage.

He has been making toad sausages which he drops into the bush - strong enough to make the native animals extremely sick, but not kill them.

"Whenever you eat something and are violently ill, it sticks in your memory," he said. "It's the same with animals. Quolls are very quick to learn, but even crocodiles are changing their eating habits."

It's evolution on steroids.

They're also experimenting with putting baby cane toads at the front of the migratory spread.

"As it stands now, it's the big adult frogs that are at the invasion front; they're bigger, faster, stronger and carry greater toxin," Professor Shine said. "So we're placing baby cane toads ahead of the invasion front so the native animals get to eat them first.

"This way they get less toxin into the system and get a chance to learn not to interfere with cane toads. It's a bit like the sausage approach."

This too seems to be having a positive effect on wildlife numbers.

And the other very promising approach has been to play on the cane toad's natural tendency.

"Cane toad tadpoles are carnivorous," Professor Shine said. "So the last thing a hungry tadpole wants is for 30,000 eggs to suddenly hatch and have that many more tadpoles vying for food. So they eat the eggs. If we can get the tadpoles and eggs together, we can let nature take its course."

In the meantime, we might as well accept that they've found their way to the Hunter. But the professor says the world isn't about to fall in.

"Cats, foxes, climate change, invasive weeds, water quality ... these are all far bigger problems," he says. "I'm not playing down the cane toad problem - everyone will feel pain if they lose their pet - but these other issues are more pressing for sure."

So, will there come a time when we have to protect our pets with a cane toad sausage?

"I think if I were in an area where cane toads are prevalent, then quite possibly, yes."

Cane toad sausages in the fridge? Who'da thought?